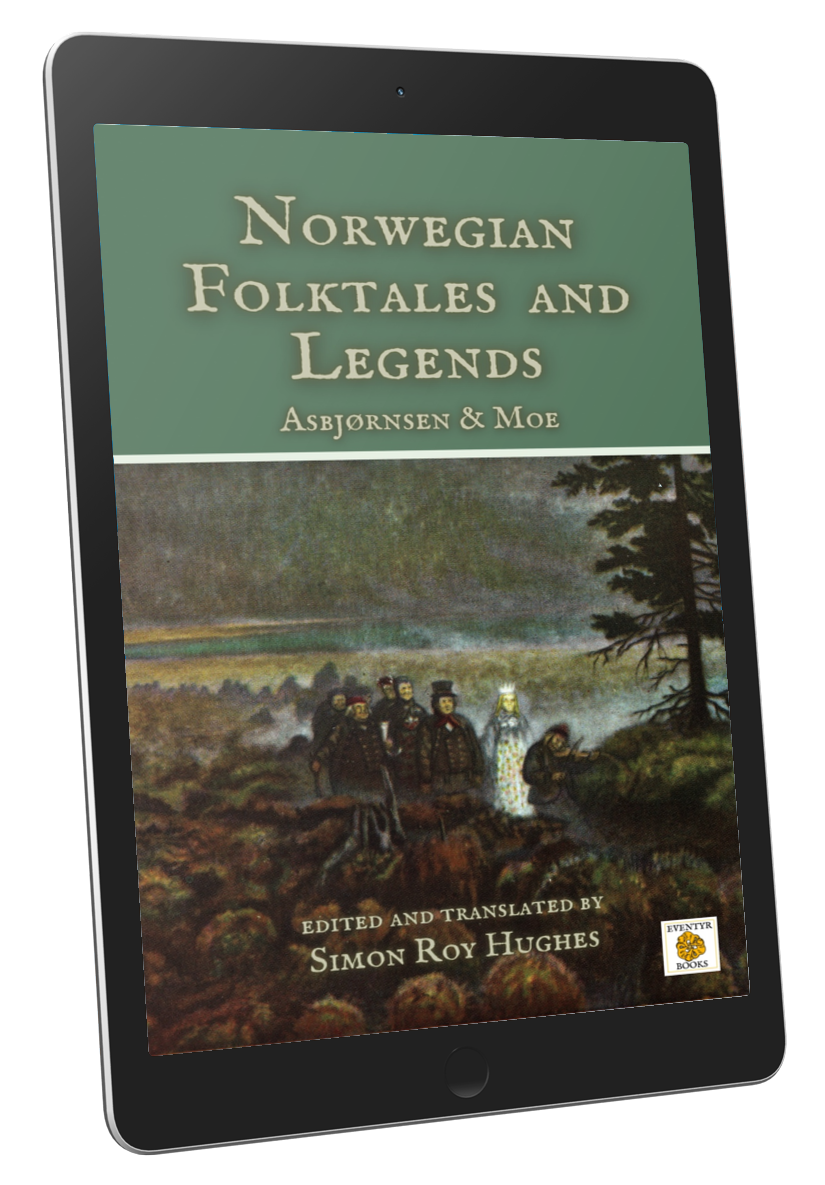

This morning, I sent off my prefaces for editing, which are the last of the texts from the annotated edition of The Complete Norwegian Folktales and Legends of Asbjørnsen & Moe. When the edits are done, there will be nothing to stop me from publishing, which is at once an exciting and unnerving prospect.

In my prefaces, I have resisted the temptation to attempt an analysis of the collection; if I ever decide I am capable of doing such a thing, it will have to be at a later date. Instead, I write about the publication histories of the stories in collections, beginning in April 1837, when Asbjørnsen & Moe agreed to embark on their publishing project, and ending with the death of Asbjørnsen in 1885. I also write about the history of the folktales and legends in English translation, and how my intention has been to improve upon the efforts of translators who have not paid sufficient attention to the provenance of their original sources. So whilst they have attempted to denaturalise the folktales and legends, I have always had an eye to the foreign origins of these wondrous texts, and the greatest respect for the care and attention by which they have come down to us though the oral record.

For these are not mere stories. At some point back in time, a particular listener must have considered the folktales and legends they heard important enough to recount for a younger generation. And someone from that younger generation thought the same. And so on. In certain cases, we know that this line of storytellers goes back as far as 2000 years, and is distributed across the world, so that we find stories similar to those we have in Europe in places as far flung as India, Mongolia, China, and Korea. Storyteller by storyteller, these stories have been sent forwards in time, and spread to the corners of the earth. Perhaps each raconteur only thought of telling this tale to that person, but from our perspective at the end of the line, we can glimpse a broad, long-standing folk movement to spread these stories. I believe therefore that we are obligated to honour this aspect of transmission, and one way of doing so is by openly crediting the origins of the texts.

It is said that there was a nisse on the farm of Bure in Ringerike some time ago, who did the people there a lot of good. Not only did he groom the horses and tend the fire and lights, etc., but he even took on the job of a driver. Here’s how things went.

It is said that there was a nisse on the farm of Bure in Ringerike some time ago, who did the people there a lot of good. Not only did he groom the horses and tend the fire and lights, etc., but he even took on the job of a driver. Here’s how things went.