Tl;dr: Some books of fairy tales give no return on the invested effort.

Anna Winge (1860–1921) was born in Christiania, the niece of the national poet Johan Sebastian Welhaven on her mother’s side. She studied music and song under Thorvald Lammers and Desirée Padilla, then worked as a singing teacher. She founded a choir, wrote an opera, published a hymn book, and generally did musicky stuff.

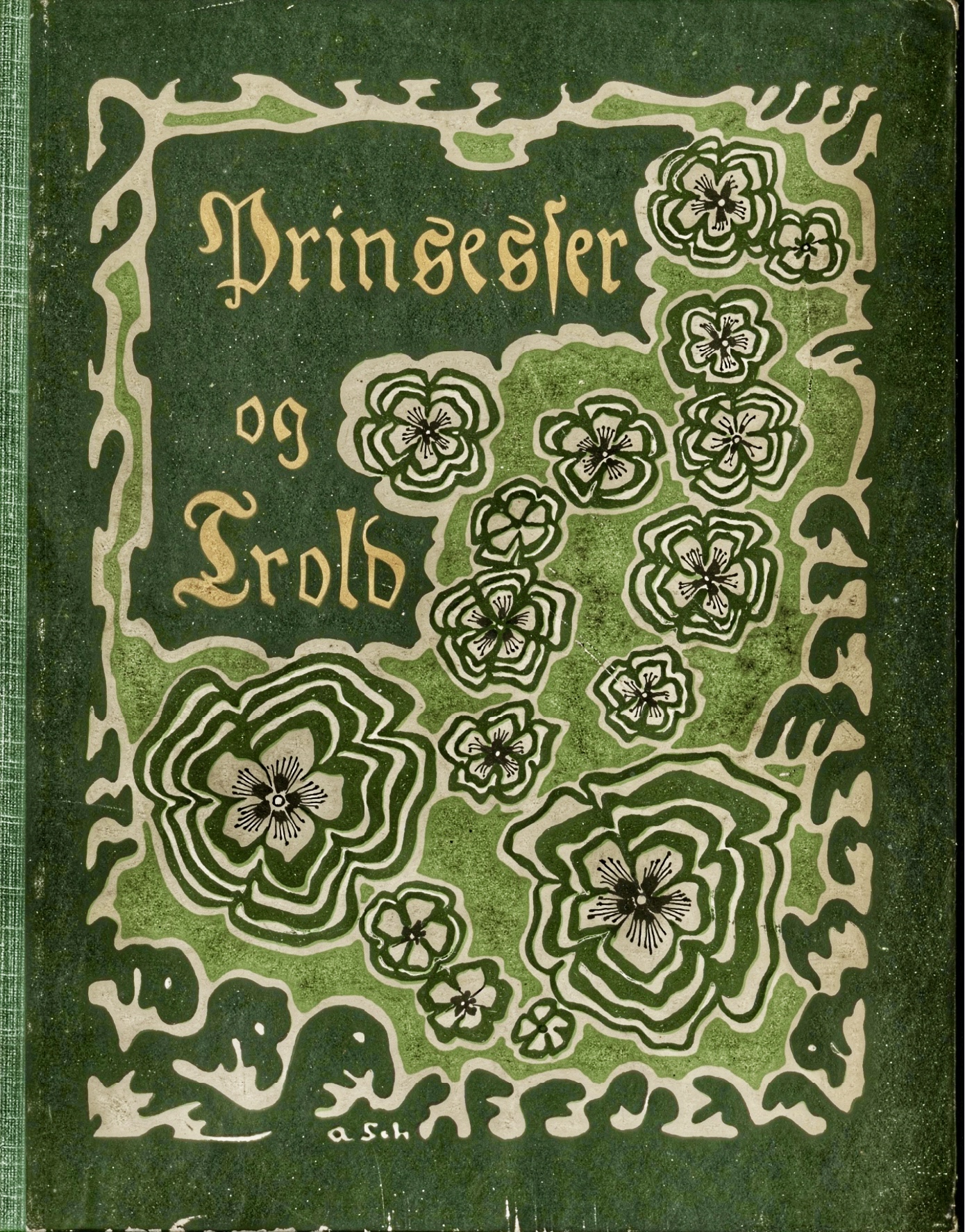

In 1901, she published Prinsesser og trold: eventyr for børn, a brief collection of fairy tales for children.

Ever on the lookout for a new translation project, I picked up a rather worn copy of Prinsesser og trold so that I might investigate these stories; would they entertain enough today to warrant translation and publication? I have consequently translated two of the tales, “The Lily Princess” and “The North Wind and the South Wind,” which are the first and fifth texts respectively. (I find that translation is the most effective method of deep-reading, as it forces me to properly understand what I am reading before formulating the same thought in a different language – no shortcuts.) And I discovered that these stories will just not cut it.

In “The Lilly Princess,” as an example, the plot does not hold together. We begin with a lovely description of a castle garden in which grows an apple tree that bears golden apples (real gold) that the children of the kingdom gather every autumn, much to their and the king’s delight. And that’s the last we hear of that.

Now, there is also a tarn at the bottom of the king’s park (in which lies his garden, in which stands his castle), where dwelt a troll, perhaps a hundred years ago. The troll stole away the princess of the day, and the king her father struggled to banish the troll at last. There is a description of the cross that king erected to ward off the troll’s return.

Well, the prince of the present has to go out to look for a wife, but just as he is about to set out on his quest, his mother falls very ill, and apparently, there is a single nightingale in all the kingdom that can save her life. How he heard of the nightingale is not related.

Off he goes to find the nightingale; a princess for a wife can wait.

Anyway, this nightingale, which of course the prince does find, causes him to weep a tear, which falls on to a lilly growing at the foot of a linden tree. The lily turns into the princess abducted by the troll. The nightingale itself is apparently a singer who has been been enchanted by enchanter unknown for a hundred years. At the end of the hundred years, she will turn back into a singer and become world famous. But we hear no more about this. They all go back to the castle, the nightingale sings the queen better, there is a wedding, and they all live happily ever after.

So the apple tree at the beginning and the nightingale at the end are both narrative dead ends. Add to this major turn off the language that does its best to imitate Hans Christian Andersen’s pathos (but falls short), and perhaps you’ll understand why I gave this brief collection a pass.

The other tale I translated, “The North Wind and the South Wind,” doesn’t have a plot at all.