In the olden days it was customary in the settlements that everyone should go to a feast on Christmas Eve after they’d left church. No one should sit alone at home; either you’d invite guests yourself, or you’d be a guest at a neighbour’s or an acquaintance’s somewhere. But there was once a man at church who had expected to be invited to a feast, yet unfortunately, it turned out that no one thought of him or remembered to invite him. “Oh, that’s no bother,” thought the man, “if no one wants to invite me, then I shall invite others. I must certainly not go home alone.” So he went around looking for various acquaintances, asking them to be so kind as to come home with him, but things went no better than that everywhere he went, he arrived too late, and there was no one who could go with him.

The man was then both angry and sorrowful. He didn’t know what he should do, and as he walked and wandered around the churchyard, he happened to kick at an old skull which lay there at his feet. For it often happens when a new corpse is burried in an old cemetery, that an old head may be thrown up and come to lie in the upper soil. “Come on, then, since no one else will,” said the man, as soon as he saw the head.

The head then rose up from the ground and hovered around the man like a bird, and then it went home with the man from church. It stayed with him both at home and abroad, both at sea and on land. Wherever the man went, the head went too, hovering all around him.

Once, when the man was in the woods, he heard that the head laughed, and the man asked what it was laughing at, but received no answer.

Another time the man was in church, and things went the same way. It was quiet as the parson stood in the middle of his sermon in the pulpit, and the man heard the head laughing, and he asked it later what he had laughed at, but neither then was there any word or breath to be heard.

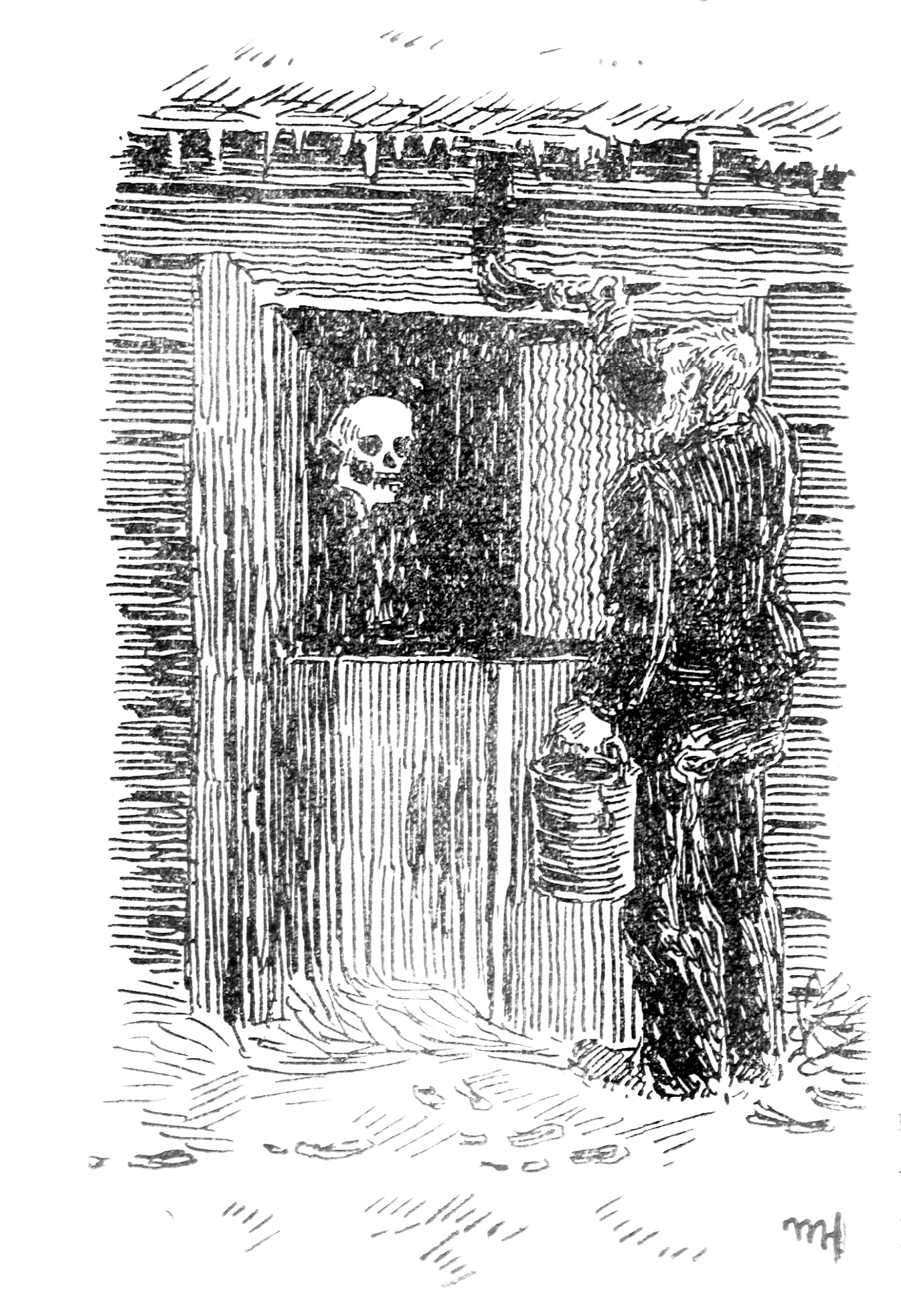

As time passed, as it is wont to do, summer came, then winter, and finally came Christmas again. When Christmas Eve arrived, the man went out in the twilight and painted crosses on the doors of his barn and storehouse and all the outhouses. And when he had put the last cross on the storehouse, the head laughed loudly.

“If only I were so wise that I knew what you were laughing at,” the man said.

Then the head began to speak, saying that they would soon be parted. The man said that there was much he had a mind to know, but first and foremost he wanted to know what the three laughs were supposed to mean.

“I’ll tell you,” replied the head. And then it said, “The first time I laughed was last spring, when you were cutting down a birch tree up in the woods. Then the sole of your shoe tore, and you knew no better than to dig around the foot of the birch and pull up a root to tie the shoe together so that it would stay on your foot until you got home. If you had known what I knew, then you would have dug a little deeper. For there was a chest beneath the root, so full of gold and silver that you could have bought the whole settlement and several settlements with it. And then you would have stopped wearing shoes that have to be together with birch roots.

“I began to laugh at how dull a man can be, who cannot see his fortune, even though it is so close that he need do no more than turn around, reach out his hand, and grasp hold of it.

“Then there was the second time, when you were at church this summer. Then again I saw something that you didn’t see. It was after the congregation had come in, and the parson had begun to speak. Then Old-Erik came, too, and sat out on the threshold; he had a big calfskin to write on. And he wrote up all the witches who were inside. And there were so many that that he did not have enough room on the skin for them all, and so he bit along the edge of the skin, to stretch it out until it was big enough. Just as he carried on so, and chewed and bit, the skin slipped out from between his teeth, so that there was a big chomp. Then I began to laugh – and you would have done so, too, had you seen and heard it.

“Then there was the third time I laughed, which was today when you put crosses on the walls. Then I laughed at the little trolls that began to flee from the mark of the cross. They looked like great flocks of rats and bats coming out of the buildings, and they hopped and crawled out through all the windows and all the gaps in the walls. You can imagine what a fine company it would have been that should taken refuge in your house for the holiday! But they flew across the ground, so eager they were to hurry, and run about, looking for shelter in another place. And now it’s free and peaceful in all of your buildings, so there’s no need to worry, neither for folk nor for cattle.

“Now I cannot take the time to talk to you any longer, for it is time for me to go to another place. And so my thanks for inviting me to your feast.”