Back in the days when I was still considering a traditional publishing contract for The Complete Norwegian Folktales and Legends of Asbjørnsen & Moe, one of the questions agents and publishers often asked was “Why you?” meaning, I suppose, why does the author want to publish the submitted work. So I shall try to answer that question here.

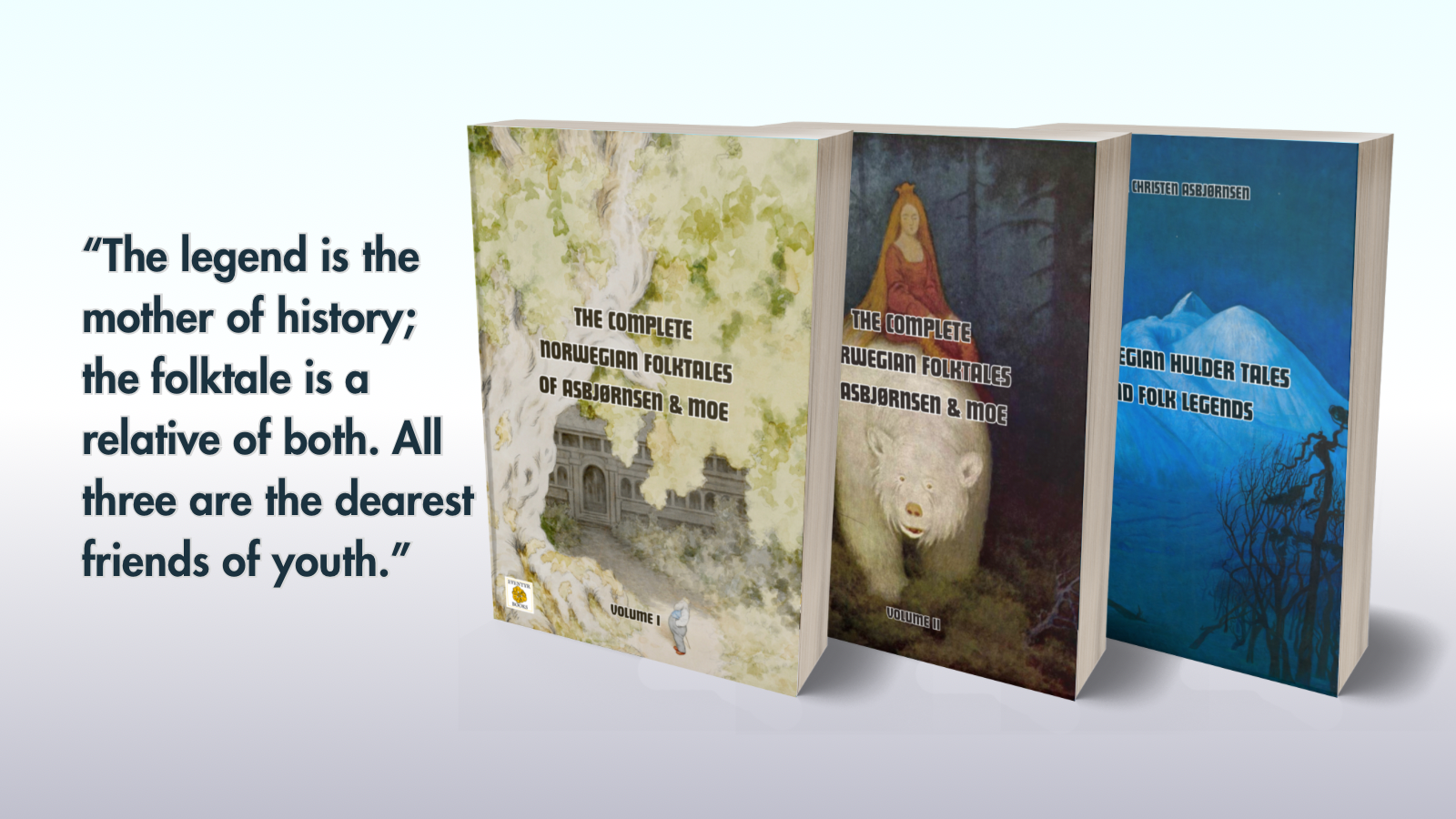

The most obvious reason for my wanting to publish The Complete Norwegian Folktales and Legends of Asbjørnsen & Moe is because it has never been done. There have been selections of the whole collection, yes, but no one before me has taken the trouble to immerse him or herself in the material and see it through to the end. My most personal reason for doing it is that it deserves doing. The Per Gynt legends have never appeared in English before, despite the enthusiasm (especially in America) for Ibsen; the hulder folk (fairies/ elves?) have never been properly introduced to an English-speaking audience; the Norwegian cunning arts are more or less unknown; the troll, that cornerstone of Norwegian folklore, has never been portrayed in its fulness.

And then there is the sorry state of the translations that have appeared; unnecessary inaccuracies abound. In the original, the cat is a female, not a tabby; the horse is a buckskin, not a dapple; the goats have an old Norwegian name, not a repurposed English adjective, and humans take them to where they are going – they're not just wandering around by themselves. Lastly in this regard: THERE ARE NO GRIFFINS IN NORWEGIAN FOLKLORE.

Indeed, the job I have taken upon myself has never been done before, and it deserves doing and doing well.

So what makes me the person to do this job (another favourite question from publishers and agents)?

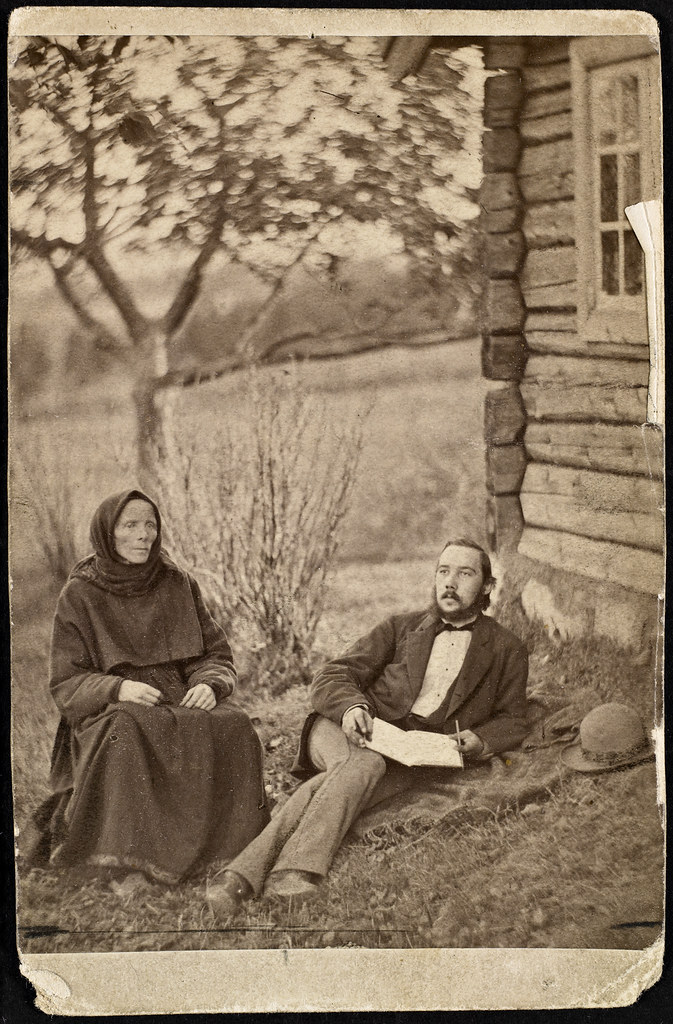

The answer is simple: I am best qualified and best positioned to do it. In a couple of months from now, I will have been living in Norway for 32 years. I lived in Sweden for about a year before that. I earned all of my education in Norway – most of my studying (literature/ philosophy/ religion/ education) was accomplished in Norwegian. (I also studied English for the three-and-a-half years.) I have lived with two Norwegian women (consecutively), brought up 4 + 2 children. I have taught several thousand Norwegian children, youths, and adults in the Norwegian school system. I read and write Norwegian and English at comparable levels. I would not consider myself a native speaker of Norwegian, but I’m as close as you can get without having been born here.

And of course, there is the love I have for the material. I heard the story of the billy goats and the troll as a child, of course, and I have some vague school memories of stop-motion puppets eating porridge, but it was while I lived in Bergen for six months in late 1992 that I was properly introduced to Asbjørnsen & Moe, through the medium of Ivo Caprino’s short animated films. I was hooked, and have been ever since. Geekily, nerdily hooked. I still wander around with my head full of tusses and trolls.

I am near completion of the project of publishing the full Asbjørnsen & Moe collection, and I can honestly say that every single session of translation, editing, and writing has been a pleasure. Unlike the epic journeys within the tales and legends, my road has been a straight one. Uphill at times, yes, but I have always been able to see my destination in the distance, and I have always known I am going to reach it.

At the time of writing, I have one introduction to complete. Then my introductions need editing. Then a last edit of the completed volumes, making sure the images don’t disturb the pagination, etc. And then the project shall have been accomplished.

Man, what a ride it’s been!