This outlying creature of Norwegian folklore is the topic of a book I have been wanting to produce for a long time. It has been delayed, of course, by the mountain of work that Asbjørnsen & Moe gave me. However, now that I’ve mostly finished with them (at least for now), I have time and energy to expend on such projects.

The book itself is a compendium of texts – both folkloric and literary – that deal with this enigmatic psychopomp (for I think we must be able to term it thus). A detailed introduction will not be necessary, either, for Andreas Faye has us covered (see below). I am still meditating on how to include in a paperback the information behind the links. Perhaps this one will be a hyperlinked ebook only – I haven’t yet decided.

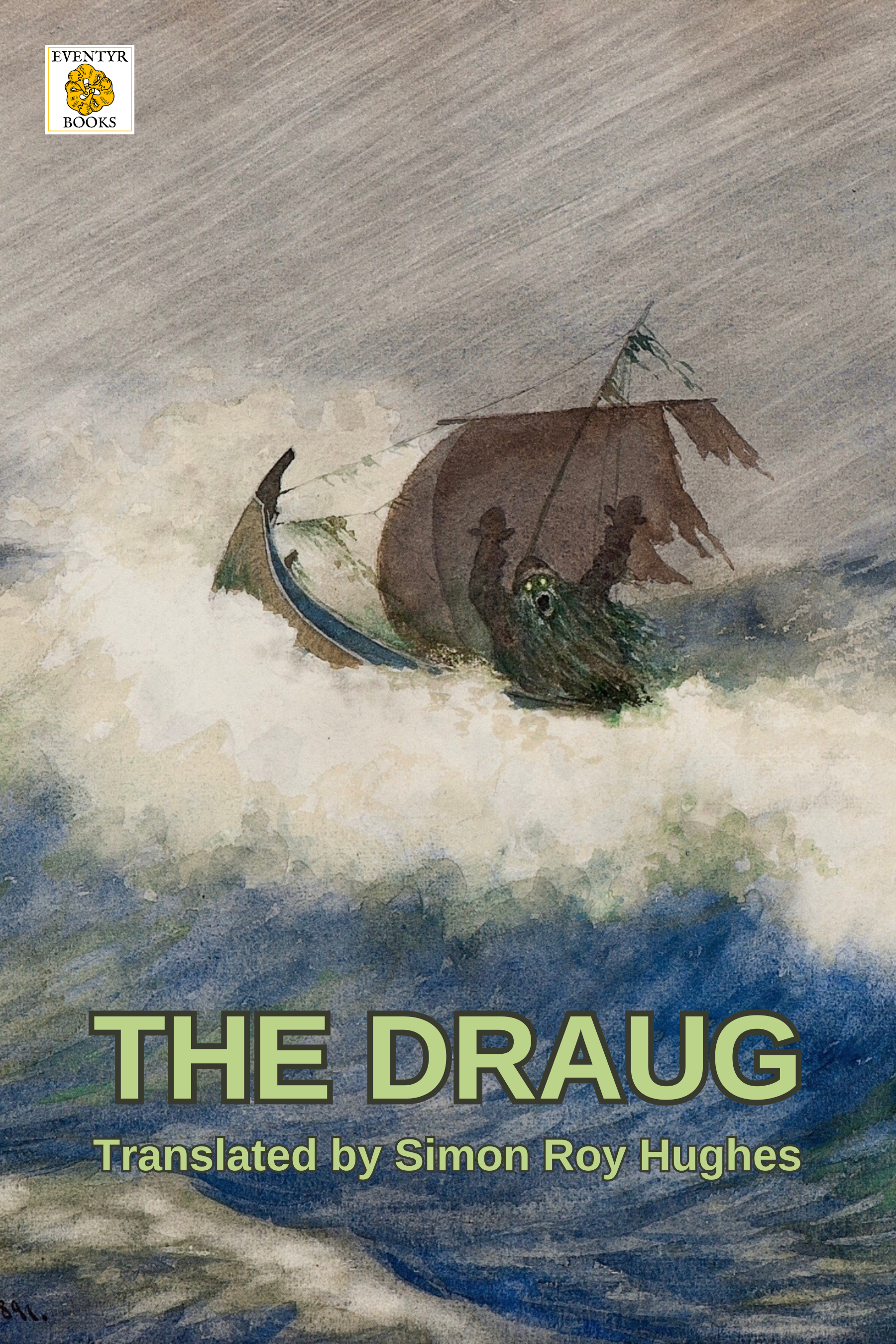

The Draug

(From Andreas Faye. Norske Folke-sagn. 1844, p. 7f.)

The concept of the draug varies. South of the mountains1 it is widely considered to be a white ghost [gjenferd], or a fylgje that forebodes death, and accompanies the fey wherever he goes. And sometimes it shows itself as an insect, which in the evening gives off a whistling sound. Herjus Kvalsot’s “draug” haunts the place where he was murdered, at Herjusdalen in Hvidesø, and came to his home one Christmas Eve, crying:

Better to walk at Kvalsot on a newly-swept floor

than to lie in Herjusdalen in unconsecrated ground.2

North of the mountains, on the other hand, the draug is nearly always to be found on or by the sea, and to some extent it thus replaces the neck. The fishermen from Nordland have many dealings with the draug. They often hear a fearsome scream from the draug, which sounds like: “h – a – u”, and also, “so cold!” and then they hurry to land, for the scream forebodes a storm and misfortune at sea.

The fishermen often see him, and describe him as a man of average size, who is dressed in the typical clothes of a seaman. Most folk from Nordland say that he has no head. Folk from Nordmøre, on the other hand, admit him a tin plate on his neck instead of a head, with burning embers on it for eyes. Like the neck, it can take on different forms. It prefers to haunt the boathouses, where it most often dwells. In these, and in the boats, the fishermen sometimes find a kind of foam. This is assumed to be the draug’s vomit, and the belief is that it warns of a death.

Note: In the Old Norse language, it is called the draugr. For the Icelander Thorstein Skelk, a contemporary of Olaf Tryggvason, the draugr of one of Harald Wartooth’s champions roared most gruesomely, as if from Hell, but sank down into the earth at the sound of the church bells. It is also called at that place “Dolgrimm.”3 (Fornmanna sögur, III, §200.)

Odin is praised in Ynglinga saga [§7] for being able to waken the dead from the earth, and was therefore called “draugr dróttinn” [revenant-sovereign]. In Hervarer saga [Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks] the draugar are spoken of as the ghosts [gjenferd] of the heroes that dwelled in the burial mounds (compare Hrómundar saga Gripssonar §4). The draug thus appears to be one’s fylgje, which leads the dead to the very grave.

-

[Norway is sometimes divided horizontally at the Dovre mountains in Gudbrandsdalen.] ↩

-

[Faye’s source is unknown, but likely oral, as no Norwegian folklore had hitherto been published. The account has subsequently appeared in Rikard Berge’s Norskt bondeliv i segn og sogu, p. 1–3]. Herjusdalen is located within the municipality of Drengedalen in Telemark.] ↩

-

[“Dolgrimm”: This word appears to be a compound of “dolg” (foe) and “grimm” (fierce); however, I have not been able to find it in transcriptions of the original, nor in Danish translations of “Þorsteins þáttr skelks” (“The Tale of Thorstein Skelk”) in the Fornmanna sögur (Sagas of the Ancients). I can only speculate that Faye has somehow mistaken the Old Norse “draugrinn,” which is merely an inflected form of “draugr,” for a discrete noun.] ↩