When I was preparing and publishing Erotic Folktales from Norway (2017), the lack of LGBTQ+ presence in the collection was one of the things that bothered me. Having said that, one tale in that collection does take up feminist, queer, and even transgender themes; “The Girl Who Served as Soldier and Married the King’s Daughter” is a well-established folktale, having been “continuously told for about three thousand years,” and widespread, with variants having been collected from “locations as distant from one another as Chile, Norway, and Russia.”1 So the folklore is out there, despite any attempt to suppress it.

Knowing this, I was surprised when, a few years ago, a Forbes article popped upon my radar, “Why This Charming Gay Fairytale Has Been Lost For 200 Years,” the point of which was to promote the work of Pete Jordi Wood, and his book, The Dog And The Sailor (originally self-published, 2020; Puffin, 2024). My surprise was not that this folktale existed, but that it had allegedly already been published – twice in Danish, but also in Finnish, Finnish-Swedish, Dutch, Frisian, and German – and then “lost.”2 How does that even happen? So, since I can read Danish, I went looking for the sources. I found one of the published variants on my bookshelf, and discovered that it was not obviously queer.3 In fact, once the hero has saved the prince and the king, he decides to take the reward and leave the country.

I had difficulty locating the second variant, and eventually gave up looking, assuming the gay stuff must be in there.

Fast forward to yesterday, when Liz Gotauco published a video promoting Wood’s book, which has now been picked up by Penguin imprint Puffin. I thought I’d have another look for the second variant, and this time I found it on Google books.4 And again, I am puzzled that the folktale as published does not reference any homosexual love. In this variant, the hero refuses half the kingdom, travelling home to his parents instead, where “they lived so well together, and perhaps do so still, even today.”

What then is going on?

I decided to look more into the work of Pete Jordi Wood, and discovered that his considerable skill in self-promotion has probably taken him into the realms of misrepresenting his source material. He is able to do this because his sources are in languages other than English, which relatively few Anglos can verify. (I also wonder how Wood went about “translating variations of the story from Danish, German, Frisian, and others.” Is he a polyglot? We deserve to be informed, if we are to accept the account of his method.) Puffin, which has also picked up Tales From Beyond the Rainbow, Wood’s collection of ten LBGTQ+ tales, is probably most forthright: “Pete Jordi Wood has combed through generations of history and adapted ten unforgettable stories” (my emphasis).

Assuming the rest of Wood’s account is more or less true (and however would he have found these Danish tales, unless he had waded through Thompson?) I think it probable that he has found ten folktales that are ripe for queer readings, then retold the stories from that perspective. Only this and nothing more.

In my (white, hetero, middle-age, middle-class) opinion, the misrepresentation of the material serves to undermine Wood’s achievement in writing and publishing these stories. He could stand forth as a modern, proudly gay Hans Christian Andersen, writing bold new fairy tales for his people, who sorely deserve to meet themselves in literature. Instead, he has decided to downplay his involvement, claiming that he has uncovered something “ancient.” Yet perhaps it is thus more difficult to summarily dismiss the stories as merely “gay.”

-

Psyche Ready. “She Was Really the Man She Pretended to Be”: Change of Sex in Folk Narratives. MA Thesis. George Mason University, 2016 (p. 1, 28). ↩

-

Hans-Jörg Uther. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2011 (vol. 1, p. 314f) ↩

-

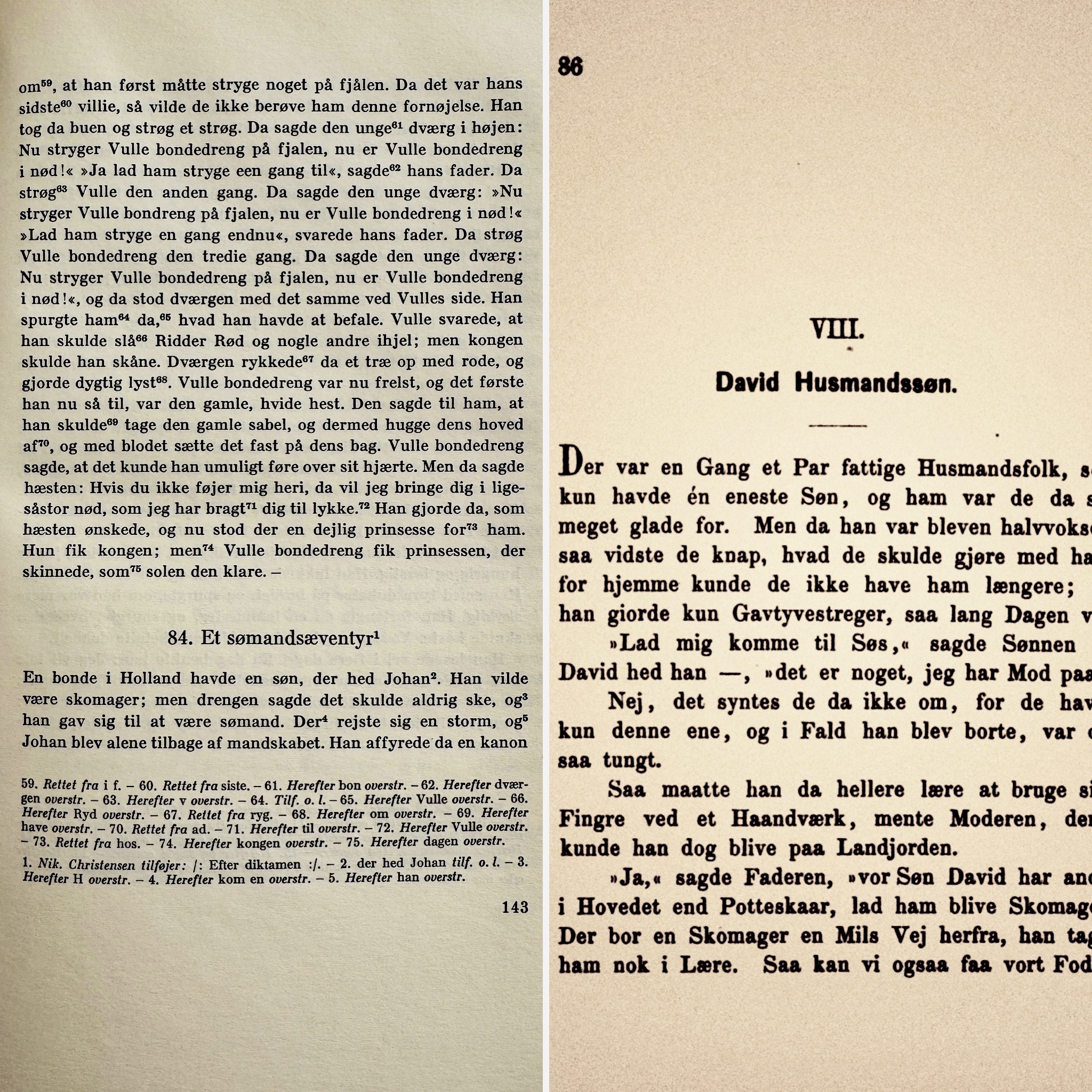

“Et sømandsæventyr” in Nikolaj Christensen. Folkeeventyr fra Ker Herred. København: Laurits Bødker/ Ejnar Munksgaards Forlag, 1966 (vol. 2, № 84, 143ff). ↩

-

“David Husmandssøn” in Jens Kamp. Danske Folkeeventyr. København: Fr. Weldikes Forlag, 1879 (№ 8, p. 86ff). ↩